Dr. Neena Prasad is a rare artist – she possesses not only a remarkable breadth of experience in the classical arts, but also a depth in each domain that is simply astonishing. She has trained with doyen Gurus in the classical dance forms of Kathakali, Mohiniyattam, Bharatanatyam, and Kuchipudi, and has awards and accolades that are a testament to her excellence in each of these forms. Dr. Prasad is also a lauded academic with doctoral and postdoctoral research experience in dance, as well as several articles and papers on a variety of topics to her credit. She runs two esteemed dance schools in Thiruvananthapuram and Chennai. She has created new pedagogy, compositions, and productions in Mohiniyattam, cementing her legacy as a pathbreaker in this art form, while adhering to its core with deep conviction and integrity. It was an honor to have a relaxed conversation with her about her training, performing experience, new choreographies, and upcoming performance in Cambridge, MA, co-produced by Rasik Dance Concert Series and The Dance Complex. It is an extraordinary opportunity for the Greater Boston audience to witness an artist of Dr. Prasad’s repute in a concert with a live orchestra this weekend.

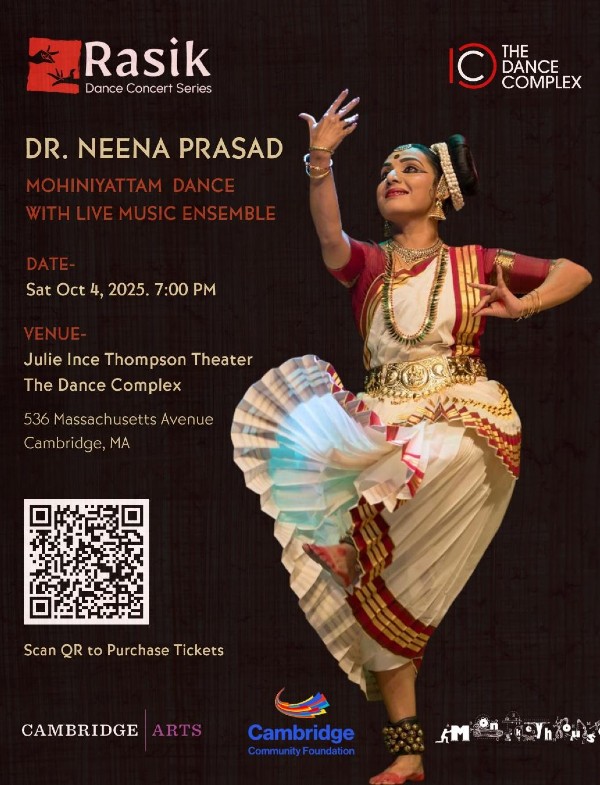

Saturday, October 4, 2025, at 7:00 pm

Julie Ince Thompson Theater

The Dance Complex

536 Mass Ave, Cambridge, MA

Click here to learn more and purchase tickets.

Here are some highlights from our conversation.

Sunanda: You have trained in-depth in Bharatanatyam, Kuchipudi, Kathakali, and Mohiniyattam from the best gurus. When did you first start dancing, and in which of these styles? What made you pursue training in these multiple art forms, and how did you manage what must have surely been a very intensive learning process? How did you reconcile the sometimes contradictory demands on your body in the pursuit of these dance forms?

Dr Neena Prasad: I started dancing at the age of three. My mother was waiting for the day when I could commence dance lessons since I was a meek child who did not show much interest in regular studies. She enrolled me in both Bharatanatyam and Kathakali classes in Thiruvananthapuram. I had my Kathakali arangetram at the age of 11, and it was unusual because it was a performance of ‘Kuchela Vritham’, where my brother played the role of Kuchela and I played Krishna! Subsequently, I assumed minor roles in many Kathakali plays and also witnessed long performances that would start in the evening and run late into the night. When I was in 10th grade, I was selected to be the lead actor in All India Radio’s children’s Kathakali group. Thiruvananthapuram has a strong affinity for Kathakali, and even the children of the royal family used to train in it. In this manner, I continued with some minor training in Mohiniyattam and a primary focus on Kathakali throughout my school years, and I won many local awards.

I was keen to go to Chennai to learn Bharatanatyam and Kuchipudi. Since my father was a professor at the college where I enrolled, he was able to arrange for me to study remotely for the most part, only coming to Thiruvananthapuram to attend exams and such. I stayed with my aunt in Chennai and enrolled with Sri Adyar Lakshman for Bharatanatyam and Sri Vempati Chinna Satyam for Kuchipudi. The first few months of training were miserable for me because I lacked proper technique in Bharatanatyam, and my Kuchipudi showed a heavy Bharatanatyam influence. Many times, I was in tears and ready to give up, and I wrote to my mother asking her to abandon any dream that I would develop into a good dancer. She wrote back encouraging me to seek enjoyment in my dance, and to celebrate small wins in my practice. I took this advice to heart and continued working hard in my classes for the next three years or so, spending all day every day with my two Gurus. Slowly but surely, I made progress and started getting performance opportunities in both Bharatanatyam and Kuchipudi.

Sunanda: When and why did you pick Mohiniyattam as your main art form?

Dr. Neena Prasad: On one of my trips home, I watched a Mohiniyattam performance by Sugandhi teacher, and I remember feeling renewed respect for the art form. I obtained a senior scholarship from the government to pursue training in Mohiniyattam, and I took lessons with Sugandhi teacher in Ernakulam.

In 1994, I was invited by the Tamil Isai Sangam in Madurai to do a performance that was half Mohiniyattam and half Bharatanatyam. Serendipitously, I had a chance to meet and work with musician Sri Madhavan Namboothiri at that performance, and I feel that the opening piece we performed on Saraswathi and the warm audience appreciation somehow cemented my relationship with this style of dance.

Between 1994 and 1998, while I was working on my PhD in literature at Rabindra Bharati University in Kolkata, I continued to train intensively in Mohiniyattam with Kshemavathy, who had a very intellectual approach to her choreography. In 1998, I was invited to dance at the Soorya Festival, and Sri Madhavan Namboothiri helped me create new pieces, including one on a modern take of Kalidasa’s Shakunthalam. This performance was a landmark moment in my career, with the press carrying prominent reports and calling it a pivotal shift in the presentation of Mohiniyattam. After that, there was no looking back, and even Adyar Lakshman sir who taught me Bharatanatyam, advised that I focus on Mohiniyattam, which seemed to be the most natural fit for me. More milestone concerts and press acclaim followed in Chennai, and I received the best dancer award at the Music Academy festival in Jan 2001. From then on, I received invitations to perform from organizations all over the country.

Sunanda: Apart from your Gurus, who are the people who have supported your pursuit of the arts? Were there dancers/musicians in your family before you?

Dr. Neena Prasad: Both my grandmothers danced, but informally. My family had many musicians, and my father started the first sabha of Thiruvananthapuram. I came from a middle-class family where my father was the primary breadwinner, but my mother took a very keen interest in our training in the arts, and she was my driving force.

When I was doing my PhD, I met art historian Mohan Khokar. After watching me dance, he encouraged me to stick to Mohiniyattam because he felt that I was uniquely equipped to advance the art form. Eminent art critic, Subbudu, voiced the same opinion after watching me perform in Delhi, and he urged me to work with Carnatic music rather than Sopanam music from Kerala. I was also praised by art critic Leela Venkataraman. These words from eminent connoisseurs came at a formative time in my dance career and boosted my confidence that I was on the right track in terms of my approach to Mohiniyattam.

Sunanda: Do you think your proficiency in literature informs your presentation of dance pieces today?

Dr Neena Prasad: Since my father was a professor of literature, we often interacted with eminent writers in Thiruvananthapuram, and I was an avid reader from childhood. I was the first person to obtain a PhD in dance from Rabindra Bharati University (2005), and followed that with a post-doctoral fellowship at the University of Surrey, England, where I studied Post-Colonial Identity of Mohiniyattam. In 2008, Kalamandalam turned into a deemed University, and I became the first research officer there.

I have always had a deep research interest, and that impacts how I think about dance pieces and how I choose to portray various characters in role-play. For instance, when I chose to first present ashtapadis, there was a hue and cry about whether it was necessary to explore pieces that were so heavily sringara-based, given the troubled past of Mohiniyattam. I had done in-depth research into ashtapadis, and I felt I could present them in a way that would resonate with the audience. I must say that it was a very successful experiment despite the initial doubts.

Sunanda: Did you also train in classical music? How does that help you today?

Dr. Neena Prasad: I had early training in music, but never felt I was particularly suited to singing. During my training with Lakshman sir in Chennai, he encouraged me to try singing and doing nattuvangam at the same time. It was very challenging initially, but I became adept at it after a few months of intensive practice. I also took music lessons with my sister-in-law, who is a musician in Kerala and learned the intricacies of manodharma (extemporized) singing. I may not have pursued singing, but I am a keen rasika and can appreciate the nuances of traditional Carnatic music. I have also formally trained in mridangam playing, and my ear is always drawn to percussion when listening to music. I have a penchant for creating jathis (syllabic rhythmic sequences), and I can guide mridangam players who accompany me on how to embellish different dance sequences.

Sunanda: Can you briefly share your role at Kalamandalam in the revival of Mohiniyattam?

Dr. Neena Prasad: In the 1990s, there was a lot of dissension within Kalamandalam regarding the instruction of Mohiniyattam and specifically about dance works that were suitable for teaching/presentation. While one faction wanted to explore new compositions, including those on Shiva, the other faction wanted to stick with traditional works that were primarily on Vishnu. Slowly, it became acceptable to present pieces on a variety of themes, especially since the audience response to them outside of Kerala was heartening.

On one occasion, when I danced for Dr. Kanak Rele, she questioned me about a technique issue, which I realized was not quite addressed in the teaching at Kalamandalam. With Sugandhi teacher’s encouragement, I developed a full adavu pedagogy with distinct nomenclature for each movement. For instance, it is the torso movement called andolika that gives Mohiniyattam its identity. I gave each instance of this movement a unique name and technique to match. My pedagogy received accolades from none other than Dr. Padma Subrahmanyam, who told me that this is exactly what the art form had been lacking until that point. I also helped codify the hastas (hand gestures) that are drawn from the ‘Hasta Lakshana Deepika’, a medieval text from Kerala that forms the foundation for gestural acting in Kerala’s traditional theatre and dance forms.

Sunanda: Could you tell us a little about your new choreographies?

Dr. Neena Prasad: I have choreographed many new compositions. My landmark group production was Sitayana – it is based on Sita looking back at her own life journey. For the music, I introduced elements of chorus singing. Based on my own perspective, I did not assign blame to Rama for Sita’s fate. There were many moments of poignance emerging from the depth with which we depicted characters in this production. I found a beautiful padam in Kambodhi that captures a conversation between Sita and Rama, where each of them reminisces on their time in the forest with very different emotions. This makes the characters seem relatable as husband and wife to the audience, and it was extremely well received, with many in the audience shedding tears watching my portrayal of Sita.

Sunanda: What are some special pieces that we might look forward to in your upcoming performance at the Rasik Dance Concert Series?

Dr. Neena Prasad: One piece I want to present in Boston that has been extremely well received in general, is my work on Bhoomi (Earth). Dr. Pappu Venugopala Rao helped me with the lyrics for this piece. Our planet has contributed to sustaining our life generation after generation, and every aspect of our life is a gift of the Earth. We didn’t come into existence bearing even a needle point of material. Consider the Protector, Vishnu – his workspace is Earth, and his role would be meaningless without Mother Earth. Even your cell phone is produced from the Earth – minerals like silica and mica that go into it. My piece will touch on all this and more. While the narration is contemporary, the vehicle will be traditional Mohiniyattam. Ultimately, dance is a musical form and one’s sense of traditional aesthetics must be strong to create new works with conviction.

Sunanda: You have often spoken about the notion of Bani (inherited style of a dance form with a distinct, strong identity) versus an individual school’s style (one with relatively minor modifications to a bani, which stems from an individual’s aesthetic leanings). In Bharatanatyam, the notion of Bani is becoming increasingly blurred as audience reception oftentimes shapes artistic output. Some decades ago, adherence to a Bani was considered a sacred duty. But today, as power, intensity, and endurance emerge as audience preference, the movement vocabulary and choice of works presented have shifted perceptibly. Has this happened in Mohiniyattam as well? What is your opinion on whether this shift is healthy/necessary?

Dr. Neena Prasad: Bani is getting blurred in every classical art form including music. I do not want to think of Bani as something rigid, but as a guiding framework. As someone whom people watch and look up to in the realm of Mohiniyattam, I feel a responsibility to maintain the core aesthetics of the form even as I explore new compositions and ideas. There is a push to incorporate faster spins and dramatic movements, but I am not sure it is required. A performer must have the conviction that they can still charm the audience within the framework of their tradition. It is only when this trust in the impact of your tradition wavers that one starts to experiment outside of its boundaries. When doing this, one needs to question if this deviation serves a purpose. Also, an experimentation that works for a very senior artist at a certain stage in their life may not work for a young artist who lacks similar life experience. If your experiment has substance and you can make an impact on the audience with your presentation, then it serves a purpose. It must draw the audience in and make them think.

Sunanda: You direct centers for dance training in Chennai and Thiruvananthapuram. What are some of the unique attributes of students of dance today as compared to when you trained with your Gurus? Pros/cons?

Dr. Neena Prasad: The students from then and now are quite different. A mind that is accustomed to reading books and a mind that is accustomed to seeking information on a phone are quite different. When the great poet Kalidasa compared the flow of the River Ganga to the undulations of a waist-chain on the hips of a beautiful woman, he had no aerial view of the river to inform this metaphor. It was simply born of his imagination. Somehow, this ability to create poetry in movement from imagination has diminished in my opinion. There is more technical virtuosity in the current generation of students though. The increased focus on technique can shrink imagination and creativity in the long run.

Sunanda: Can you speak about how you work with your co-artists on stage, especially when you create manodharma (extemporization) sequences?

Dr. Neena Prasad: To indulge in manodharma on stage, the artist must be okay with some flaws in execution. Those ‘flaws’ do not impact a performance negatively, and the artist must trust the audience to be okay with it. The musician and dancer must have a deep understanding and rapport, but not over-rehearse. The spontaneity on stage is essential, especially when one narrates from the mind. I have a deep understanding with my co-artists who follow my intent on stage to create a seamless experience. Mohiniyattam is a visual music form – there is a certain feel to the music, and you become a part of it. This is a magnificent gift of God, and I want the audience to experience it with me.

Watch Dr. Neena Prasad in a live concert on Saturday, Oct 4 at 7:00 pm at the Dance Complex in Cambridge, MA, in a performance produced by the Rasik Dance Concert Series. At this performance, which is part of a U.S. tour, Prasad will be accompanied by a live music ensemble including: Changanasseri Madhavan Nampoothiri (Vocal); Ramesh Babu (Mridangam); Kalamandalam Arundas (Idakka), and Shyam Kalyan (Violin).

About the Interviewer:

Sunanda Narayanan is an acclaimed exponent of Bharatanatyam based in the Greater Boston area. She has performed extensively in India and the US for over three decades in over 250 public performances. She is the director of the Thillai Fine Arts Academy in Newton, MA, where several students have learnt and excelled in the tradition of Bharatanatyam. Narayanan has presented several solo and group productions with her students and has conducted lecture-demonstrations and workshops at museums, schools, and colleges in the U.S, Canada, India, and Brazil. A graduate of the MIT Sloan School of Management, Narayanan also works at WGBH, Boston.

About Rasik:

Rasik is a grassroots initiative to curate and present classical dances of India in their traditional form by artists of diverse backgrounds with the goal of integrating them into the wider cultural landscape. Conceived, created, and supported by members of the Boston dance community, Rasik strives to cultivate an informed and invested audience for Indian dance in Massachusetts and reflect the vibrant, expanding cultural heritage of our community. Through a carefully curated concert series, presented in ways accessible to a thoughtful but uninitiated audience, Rasik aims to strengthen the relationship between Indian dance forms and the larger arts community.