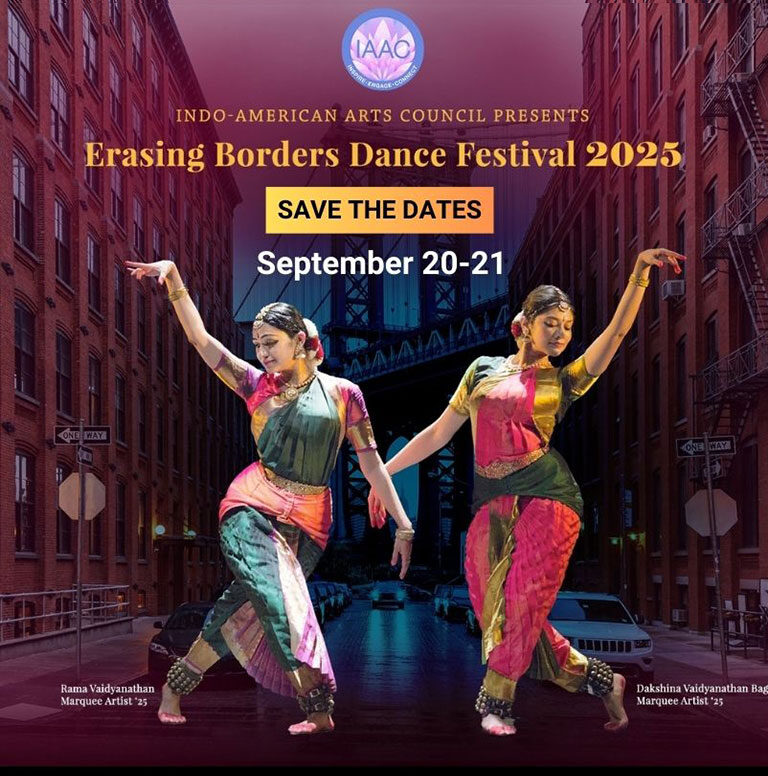

Indo-American Arts Council’s Erasing Borders Dance Festival, 2025

The two-day Erasing Borders Dance Festival once again showcased its hallmark qualities of range and inclusivity. What follows are the highlights from each evening’s performances:

Day 1

September 20, Ailey Citigroup Theater, New York City

The opening night of the annual Erasing Borders festival, celebrated for its range and inclusivity, had its share of highs and lows.

Ramya Ramnarayan’s Nrithyanjali Dance Ensemble presented a group choreography of Naṭeśa Kavuttuvam, performed by its students. The choreography and synchronization were commendable, and a few dancers stood out for their energy; however, as an ensemble, the performance did not fully capture the emotional gravitas that this powerful composition calls for. It didn’t help that the lighting obscured facial expressions. Even so, some of the dancers displayed a promising spirit, and with stronger production values, the group has the potential to grow into a compelling ensemble.

The Odissi solo by Trina Sarkar epitomized the unhurried grace of the form. Performing a Pallavi choreographed by Guru Kelucharan Mahapatra, she carried it off with effortlessness and sensitivity to both the musical composition and the choreographic structure. While one wished she had chosen a piece that also showcased her abhinaya, kudos to this accomplished dancer for embodying beauty and bringing the signature sensuous tones of Odissi into her movement.

Among the evening’s highlights, the standout group performances came from Kalanidhi’s Kuchipudi ensemble with Ananda Tandava and Chitresh Das’s Kathak Dance Company.

The Kuchipudi dancers, Sriyuktha Ganipeni,Anjana Kuttamath,Mytrey Nair,Pragnya Thamire, and Deviga Valiyil, performed Ānanda Tāṇḍavam:the dance of bliss, with perfect synchrony, skillfully using the stage space to infuse the choreography with energy and joy while evoking the emotional grandeur and intensity the Tāṇḍava embodies. Soft yellow lighting enhanced the performance, underscoring both power, grace, and poise.

The Kathak ensemble of dancers, Vanita Mundhra, Shruti Pai, Mayuka Sarukkai, and Kritika Sharma, presented Origins, an excerpt from Invoking the River, a mesmerizing fusion of Indian aesthetics with Western sensibilities. Gliding across the stage with the fluidity of water, the four dancers painted images of rivers diverging and converging, tributaries carving their own pathways, and fleeting glimpses of the marine world that evoked an undisturbed ecosystem. Their movements were framed by the gentle, contemplative piano composition of Utsav Lal, subtly accented by Nilan Chaudhuri’s tabla.

The most arresting moment came in the solo by Mayuka Sarukkai, embodying the river Kaveri trapped within the confines of an enclosed space. The lighting design set the tone and mood, with a spotlight casting shadows that imaginatively underscored the dancer’s ominous situation, heightening the intensity and tension of the scene. Her entire body spoke of torment and anguish, hands slapping, banging against the walls, and straining to break free. A sudden flash of bright light marked her liberation, leaving a hauntingly powerful image. The work concluded with a striking visual: the rivers converging, long strips of blue and white cloth strewn across the stage.

Priyadarsini Govind’s magnetic stage presence—her ability not only to engage audiences through performance but also to connect with them directly when she stepped forward to preview what was to come, has long been legendary. Over the decades, she has set the bar high for generations of dancers. So, when she faltered, it was disappointing.

She opened her performance with the Devi Stuti, a piece she had made memorable through her audio recordings. Musically, the verses were beautifully woven, with seamless transitions, each passage segueing into the devotional layering of the Goddess’s aspects through crisp, well-crafted jathis. Still, her performance fell short, with incomplete abhinaya phrases and uncertain posturing. In her description of Rājarājeśvarī, for instance, she drew the bow with fleeting devotion, but without completing the emotion transitioned into a goddess pose. The result lacked the energy this powerful composition demanded.

In Daśamukhi, where Rāvaṇa’s ten faces lamented his downfall, the musical texture, burdened by the singer’s overly emotional rendering, distracted from the intended rasa experience. It was in the padam Samayamide ra ra that Priyadarshini returned to what she is most renowned for: the subtleties of expressing bhāvas through the sheer power of a glance, a flick, or a fleeting smile. She invited the audience into the playful joys of what she described as a “naughty” piece, where the heroine beckoned her lover soon after bidding a tearful, albeit feigned, farewell to her husband. Here, she was in her element, every look, gesture, and stance vibrant with suggestive nuance. She concluded her recital with an Abhaṅg by Saint Bhanudasa, bringing the performance to a devotional culmination.

As an admirer and rasika, I look forward to seeing Priyadarshini Govind’s return with the emotional depth and conviction that have long defined her artistry.

Day 2

September 21, Ailey Citigroup Theater, New York City

Chandana Charchita is one of Jayadeva’s most beloved songs, extolled for its lyrical beauty and undeniable sensuous quality. At the opening of the second day, six dancers from Aparupa Chatterjee’s Odissi Dance Company presented the work in what was announced as a “Neo-classical Abhang style.” The piece opened with the śloka and showed promise; however, from the very first couplet, the rendition by Sri O.S. Arun failed to sustain the devotional and sensuous narrative, leaving the performance without the nuanced grace the composition demands. For instance, the verse “Kapi Villasa Villola” was set to tisra gati, rendered with the drive of a jati—precise but unfeeling—so that its melodic beauty was all but lost. Future iterations would benefit from more sensitive musical direction, coupled with greater depth of expression from the dancers, allowing music and movement to converge in evoking the devotional and sensuous grace for which Jayadeva’s poetry is so justly renowned.

Pranamya Suri’s presentation of Balamurali Krishna’s Oṃkāra Karinī was an energetic blend of nṛtta and abhinaya. In the anupallavi, her abhinaya clearly delineated the bīja mantras “hūṃ” and “hrīṃ” to depict the dynamic interplay between Mahiṣāsura and the goddess, while also embodying Śiva’s consort. Precise footwork, expressive abhinaya, and an underlying grace marked her performance.

In Madaari (The Monkey Master), dancers of the Rohan Bhargava’s Rovaco Dance Company, Siddharth Dutta, Devika Chandnani, Isabele Rosso, and Karma Chuki, brilliantly reframed the raw emotions of greed, violence, and the human drive to control. The work opened with imagery that felt almost sci-fi in tone—amoeba-like movements in constant flux, gestures of kissing hands, baring teeth, embracing and escaping, for a paradoxical narrative of controlled freedom. Bhargava’s choreography embraced intentional dissonance. Set against the original score by Saúl Guanipa, and inspired by the song “Roz” by Ritviz (“Come close, my love, don’t ever leave me”), rendered in a deliberately flat, affectless tone, love itself emerged as a toxic power dynamic, recast as domination and subjugation. The piece was unsettling, provoking both discomfort and a rethinking of the structures of power and intimacy too often taken for granted.

Ravija Desai’s Kathak performance of the ghazal, Naina re naina kaise bīte raina, recalled the poignancy of Farida Khanum’s iconic rendition. As an abhisārikā yearning for her beloved, she turned the accidental snag of her chunni on a hook into a tender illusion of her beloved’s hand tugging at it. While the moment was both inventive and evocative, the overall presentation required greater depth in abhinaya to anchor its emotional resonance.

Shaktya, presented by Rama Vaidyanathan and her daughters Dakshina and Sannidhi, is at heart a mother empowering her two daughters through a deeply moving eulogy to unsung heroes: Mai Bhāgho, Janabai, and two unlikely friends Phool, a Hindu, and Gulabo, a muslim—women protagonists who altered the course of history. Through evocative choreography, layered abhinaya, and imaginative lighting, Rama and Dakshina breathed life into the stories of quiet strength of women who shaped cultural and historical shifts. Yet, as Dakshina so vividly depicted, these women had their lives and sacrifices overlooked—their achievements left unframed and uncelebrated, unlike those of their male counterparts, and too often forgotten.

In the introduction of Shaktya, using mnemonics, vācika abhinaya, and the rhythms of the mṛdaṅgam ably played by Sannidhi, Rama and Dakshina framed their work in the imagery of the ten-armed Devi. Unfaltering in their vocal renditions and rhythmic precision, the two dancers—together with Sannidhi, seated just off-center as both support and witness—wove the performance into a richly layered invocation.

In her portrayal of Mai Pagho, Dakshina’s performance combined strength of conviction with deep emotional intensity. Every gesture and expression carried clarity and force, rendering the character’s courage palpable. The song, with its interwoven Punjabi and Hindi lyrics and Shri Onkar Singh’s evocative composition, lent the narrative a tone of authenticity and resonance.

Rama Vaidyanathan’s portrayal of the Warkari saint-poet Janabai revealed the vulnerability that underpinned courage: the unabashed daring required to seek one’s true love. Her abhinaya illumined Janabai’s inner world, bringing to life moments of defiance and devotion: walking the streets with careless abandon, her head held high against social censure, and her defiantly sensual tribhaṅga stance at a doorway, beckoning the Lord with an intensity that blurred surrender and rebellion. Through these images, Rama captured Janabai’s paradoxical strength, at once vulnerable and fierce.

The evening closed with Mitra, an evocation of the turbulent history of India–Pakistan Partition told through the unlikely friendship of Phool, a Hindu, and Gulabo, a Muslim: two women on opposite shores of a river, one clinging to memories of loss, the other stepping into a house no longer her own. Cross-fade lighting here served as an illuminator of three distinct scenarios—the two protagonists and the river between them. It allowed the audience to feel both their separation and their secretive convergence, holding in view the fragile balance between estrangement and empathy at the heart of this Partition story. Through nuanced performances, Rama and Dakshina Vaidyanathan illuminated our common humanity, a truth as delicate as it is urgent, then and now.

In the end, the two-day Erasing Borders Festival affirmed its place as a celebration of artistry, inclusivity, and cultural resonance.

(This review is published in Narthaki and on Global Indian Artist LLC.)

Anita Vallabh, Ph.D., is a dance critic, author, and the Founder & Editorial Curator of Global Indian Artist LLC. She is also the Creative Director of Sarang Arts for Social Justice and serves as Cultural Advisor to the Bhagavatula Charitable Trust. She is based in Boston, Massachusetts.